Ten years ago, federal judge Betty Fletcher said she would step aside. It was late in the Clinton administration, and Congressional Republicans, who’d long had it in for the left-leaning 9th Circuit Court of Appeals, where Fletcher presides, were refusing to confirm the President’s nomination of Fletcher’s son William to the same Circuit as his mother. They called it “nepotism.”

As a concession, Fletcher, then 76, agreed to take a form of quasi-retirement known as “senior status.” There are loose rules governing “senior” judges, who only have to work one-quarter time to receive full pay. Accordingly, most cut back dramatically and spend the extra time at country clubs or with their grandchildren.

“Let’s just say Betty Fletcher is having the last laugh,” says Nan Aron, president of the Alliance for Justice, a liberal Washington, D.C.–based group that monitors judicial nominations. Fletcher’s son was confirmed, but she never did reduce her caseload. Today, the white-haired, Seattle-based jurist—who over the course of her career was the first woman in the city to hold virtually every title she assumed—still hears some 620 cases a year, even as she uses a walker to get around her chambers. And she continues to be a thorn in the side of conservative interests. Last year, for example, she bucked President George W. Bush and the U.S. Navy by authoring the opinion of a three-judge panel upholding restrictions on sonar exercises said to harm marine life. The year before that, she tossed out the Bush administration’s proposed fuel-efficiency standards for SUVs and “light trucks” as too weak, writing that environmental laws required the administration to take into account greenhouse-gas emissions.

Though practically unknown in her hometown outside legal circles, Fletcher is a high-powered icon of liberalism, the likes of whom may never again get the nod for a federal bench. She’s a holdout from an unprecedented era of left-wing judicial appointments under President Jimmy Carter, after which moderates became the name of the game, at least for Democrats. For all the controversy over Sonia Sotomayor, with whom Fletcher shares some traits, the recently confirmed Supreme Court Justice is strictly middle-of-the-road compared to Fletcher.

“She’s always been a ferocious fighter,” says 9th Circuit Chief Judge Alex Kozinski, who is 27 years Fletcher’s junior. Judge Stephen Reinhardt, the 9th Circuit member who has perhaps earned the greatest enmity among right-wingers, calls Fletcher “one of the most influential” of the 48 judges in the Circuit.

The biggest of the country’s 13 federal appeals courts—by both number of judges presiding and geographic area covered—the 9th Circuit incorporates most of the West: nine states in all, including Washington, plus two Pacific island jurisdictions. The court is based in San Francisco but meets in three other cities, including Seattle. When conservatives talk about its rulings, they use words like “crazy,” “outrageous,” and “political correctness run amok.” To defuse the court’s power, Congressional Republicans have tried many tactics, including a proposal to split it into two smaller circuits—so far without success.

Fletcher is known for being skeptical of authority and ready for a fight with the highest levels of power. As Todd True—a former Fletcher clerk who now co-manages the Northwest office of Earthjustice, a legal spinoff of the Sierra Club—puts it, she insists time and again that “the government do its homework.”

Other court observers view her as a classic “activist” judge. Fletcher seems to believe “there’s really no limit to what judges can do,” says Jeremy Rosen, a Los Angeles appellate lawyer who belongs to the Federalist Society, an association of conservative and libertarian attorneys that believes in a limited role for judges based on a narrow reading of the law.

With President Obama continuing to promote many of the Bush administration’s policies in regard to expanding the powers of the executive branch, the influence of Betty Fletcher could well be critical in the months to come, as cases involving warrantless wiretapping and other legal controversies from the war on terror make their way through the 9th Circuit.

The U.S. Court of Appeals is the last stop before the U.S. Supreme Court. Any case involving federal law, or federal agencies, can be brought to a Circuit Court once a U.S. District Court has ruled. Immigration, discrimination, environmental standards, bankruptcies, Social Security claims—all these and more regularly come before the 9th Circuit, which is also a frequent stop for death-penalty cases. (California has a highly populated death row.) “We get hold of the vast majority of environmental issues,” says Kozinski. “We have oceans, mountains, deserts.”

The Supreme Court watches the 9th Circuit like a hawk. In the term that ended in June, the Roberts Court reviewed 16 rulings from the 9th Circuit, compared to a handful or fewer from most Circuits. Fifteen of those rulings were reversed at least in part.

Even so, the nation’s highest court hears only a tiny fraction of cases from the 9th Circuit, which decided 12,600 cases last year. Consequently, Kozinski says, “most of the time, our rulings stand.”

One of the areas in which the 9th Circuit, and Fletcher in particular, has had greatest impact is in enforcement of the National Environmental Policy Act, or NEPA, a law passed by Congress in 1969 that calls for federal agencies to produce environmental impact statements that examine the consequences of proposed actions and what alternatives might exist.

For example, Fletcher’s 2007 ruling that threw out the Bush administration’s proposed fuel-efficiency requirements for light trucks relied on NEPA. The ruling said that, when setting mileage standards according to a cost-benefit analysis, the government was obliged to factor in the benefit of reduced vehicle pollution on global warming as well as that of monetary fuel savings; otherwise the cost of new technologies would seem to outweigh the benefits. Referring to the short- and long-term impact assessment prescribed by NEPA, she wrote: “The impact of greenhouse gas emissions on climate change is precisely the kind of cumulative impacts analysis that NEPA requires agencies to conduct.”

Fletcher’s ruling “changed the legal landscape,” says Kierán Suckling, executive director for the Center on Biological Diversity, an Arizona group that was the lead plaintiff. While NEPA requires environmental assessments, it does not specify everything that needs to be taken into account—and global warming generally had not been by government agencies.

A month after Fletcher’s ruling, Congress, for the first time in three decades, passed a bill raising the gas-mileage minimum standards for both cars and light trucks. Fletcher’s order, which Bush did not appeal, still left the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration with the task of figuring out a system to incorporate global warming into the cost-benefit analysis it uses for new standards. The Obama administration is now working on it.

Fletcher also relied on NEPA in her decision on Navy sonar exercises. In January of 2008, a U.S. District Court granted a preliminary injunction, sought by environmental groups, restricting military activities off the California coast that, according to scientific studies, caused hearing loss and erratic behavior among whales and other sea creatures. The Navy could continue its exercises, the court ruled, but had to take precautions, such as shutting down its sonar when a marine mammal came within 2,220 yards.

The Bush administration vehemently fought the order, saying the restrictions would compromise military readiness. The President, in an extraordinary move, issued an “emergency” waiver from the court order.

The greens’ appeal landed in the 9th Circuit, where Fletcher ruled that the Navy did not have an “escape hatch” from NEPA’s requirement of environmental assessments. She also found that the Navy failed to pre-sent evidence that military preparedness would suffer. While the court owed some deference to the judgment of senior naval officers, she asserted, “a court’s deference is not absolute, even when a government agency claims a national security interest.”

“Fletcher brings to life the view that those people in the ’70s intended when they passed [NEPA],” says Michael Robinson-Dorn, director of the University of Washington’s Berman Environmental Law Clinic.

Others are more critical. Speaking of Fletcher’s ruling, John Eastman, dean of the Chapman University School of Law in Orange County, California, says, “It was contrary to common sense.” NEPA may be on the books, he says, but “Congress can’t pass any law that says the President can’t act in his capacity as commander in chief.”

“Where do you draw the line?” asks the Federalist Society’s Rosen. “What if you were in the middle of a war, and the President needs to transfer troops to a certain location where there might be endangered species?” Does a judge get to call the maneuver off?

The U.S. Supreme Court determined that Fletcher went too far. In November, by a 5-4 vote, the justices reversed her ruling, writing that the court did in fact owe deference to “senior Navy officers’ specific, predictive judgments.”

Unlike the Obama administration, Fletcher is not one to shy away from the value of judicial “empathy.” When President Obama said he wanted a judge with this quality, and his Supreme Court nominee had it, conservatives spun that to mean that Sotomayor had an expansive view of justice, and would be swayed by extraneous factors like emotion, ethnic identification, and the personal struggles of the parties involved. Obama stopped using the word.

But it’s exactly the word that those who know Fletcher well use when asked to describe what makes her stand out. “For her, judging is not purely a mechanical process with rules that apply regardless of their consequence,” says her son, 9th Circuit Judge William Fletcher. “Rather, it is a process of doing justice to individuals.”

She herself unabashedly embraces empathy, dismissing the controversy over Sotomayor, whom she considers a friend, as a “charade.”

“Now [Supreme Court Justice Samuel] Alito, when he was being confirmed, it was very important for him to show that he did have a human, empathetic side. So he said, ‘Of course, I will be influenced by my Italian background.’ And now when Judge Sotomayor comes up, it’s very important for her to show she’s not influenced too much by her background.”

Empathy, she continues, “is a matter of being able to place yourself in this situation. If you have a certain crime, it’s important to know why [the defendant] did what he did, how aggravated it was. Then you know what you’re dealing with.

“We’re not just dealing with paper,” she stresses. “We’re dealing with people.”

Clerks fresh out of law school could be forgiven for thinking otherwise. After all, appellate law deals exclusively with paper in some sense. Judges base their decisions on the case files of court proceedings that have come before. They don’t get to hear testimony from the parties directly involved in the case, or from witnesses—only attorneys. Even so, Fletcher instructs her minions to delve into the record for details.

Jorge Baron, executive director of the Northwest Immigrant Rights Project and a former Fletcher clerk, recalls that when he arrived at her chambers in 2003, he prepared to brief the judge on cases by researching relevant statutes and exemptions. Then Fletcher would ask: “Where is this person from?”

Baron says he quickly learned to broaden his research to encompass all the backstory of a case, not only personal narratives but the nitty-gritty facts that Fletcher also deemed important. His preparation did not shield him from embarrassment when the judge demanded to know exactly what went on in an Arizona swingers’ club that was the subject of a First Amendment case.

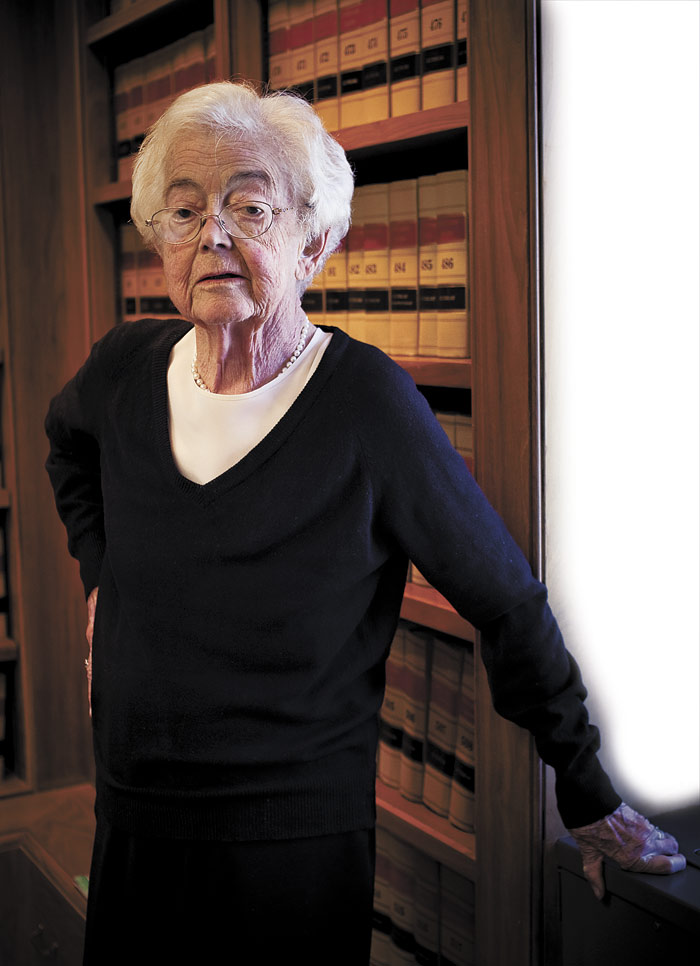

The woman at the center of these debates has a slight figure, glasses, and a distinctive, high-pitched voice that sounds something like a sparrow. On a recent day in her chambers on the 10th floor of the old William K. Nakamura Courthouse downtown, she wears a black V-neck sweater, black slacks, and pearls, and conveys a certain judicial reserve, along with an insistence that those before her do their homework. “You can look it up,” she says to this reporter as she ticks off the name of a case.

But present and former clerks say she is as warm as she is demanding. “She was the perfect mentor,” says former clerk Trevor Morrison, now a Columbia Law School professor on leave for a year to serve as an associate counsel to President Obama. She puts on a legendary annual “clerk’s weekend” at a rustic family cabin on a remote spot in British Columbia called Parker Harbour, accessible only by boat.

In court, she’s known for her respectful treatment of those who come before her. “There are judges on the court who are thought of as scary,” says Stephen Wasby, a longtime observer of the 9th Circuit and professor emeritus in political science at the State University of New York at Albany. “She’s not scary.” Her legal prose is strongly worded but free of rhetorical jabs. Even the Federalist Society’s Rosen calls her “a very nice person.”

It’s no coincidence that Fletcher has a pleasing personality and rose to power in the law at a time, the 1950s, when discrimination against hiring women was not only mundane but legal. (Congress passed the Civil Rights Act prohibiting employment discrimination in 1964.) “It was very important that you act the right role in those days,” says Jim Ellis, a legendary Northwest attorney who hired Fletcher for her first job out of law school at the firm now called K&L Gates. “A woman had to present herself in such a way that said, ‘I’m not going to shout you boys down. I’m going to persuade you.'”

Fletcher was a double anomaly in 1956 when she graduated at the top of her class from the University of Washington Law School. Not only was she a woman, but she was, at age 33, the mother of four young children. Unusual as it was for the times, by entering graduate school she was merely taking up the family profession. Her father, John Binns, was a general civil lawyer in Tacoma who encouraged her to skip school when he had an interesting case in court. Her husband Robert, a retired University of Washington professor, was a lawyer too. (Later, both her son William and her daughter Susan Fletcher French became lawyers as well.)

Once she started job-hunting, she says, she felt compelled to mention her maternal status on her résumé—”in those days they could ask you anything, so just as well to put it right out in front”—and the firms to which she sent it were equally upfront when they told her they had “no place for a woman with four children.”

Fletcher’s résumé found a different reception when it fell into the hands of Ellis, the youngest partner of what was then an ambitious but small firm. “I saw this great opportunity to get the #1 student out of UW law school,” he says. The challenge, he says, was selling a woman to his partners, who were skeptical about any female’s ability to be taken seriously by clients. A crucial person to convince was partner Charlie Horowitz, now deceased, who later became a state Supreme Court judge.

Fletcher recalls that a sympathetic professor arranged to have her sit next to Horowitz at a law banquet. As she was trying to sell herself, she says, Horowitz suddenly asked, “Is your father John Binns?” She said he was. “Then he looked at me and said, ‘This little Jewish boy would never have had a Rhodes scholarship were it not for John Binns.'” Her father, a former Rhodes scholar, chaired the selection committee that picked Horowitz, who was up against another kind of commonplace discrimination at the time.

The point of the story for Fletcher, though, has nothing to do with any epiphany that Horowitz might have had about similar forms of discrimination. It’s the irony that she landed her job, in the end, because of “the old-boy network.”

She stayed at the firm for more than two decades, eventually making partner—the first time a woman had done so at a major law firm in Seattle. She was also the first woman president of the King County Bar Association and the first woman accepted into the exclusive social group known as the Rainier Club.

“It’s not clear to me how she did it,” says Maxine Eichner, a University of North Carolina law school professor who clerked for Fletcher in the early ’90s. Even today, she observes, so many women retreat to the margins of professional life once they have a family.

Her children Susan and William explain that their grandparents moved in with them to help out when their mom went to law school. Their dad, who initially practiced at his father-in-law’s firm, came to have a flexible schedule when he became a law professor. “Ultimately, my dad took over the kitchen,” Susan says. Still, they say, their mom was around enough to keep them busy. “Idleness was not encouraged,” says Susan, who remembers family time spent digging for clams, picking berries, and then freezing and canning it all.

Then Fletcher’s life was upended by a historical event. In 1978, under the Carter administration, Congress passed a bill that added numerous judgeships to federal courts around the country. For the 9th Circuit, says Arthur Hellman, a University of Pittsburgh law professor who specializes in that court, “that was a remarkable and unique episode…Carter appointed 15 judges in the space of two, two-and-a-half years.” No Circuit got as many new judgeships. The influx transformed the court politically. “Before that, the 9th Circuit was a fairly conservative court,” Hellman says.

Carter set up nominating commissions in each district to look for potential judges. They were instructed, Hellman says, to “reach out to people who otherwise might not have been considered.” They found women, minorities, and liberals—old-school, straight-ahead liberals, not the triangulators of the Clinton years. Fletcher was a natural choice.

One of Fletcher’s first landmark opinions involved affirmative action for women. In 1979, the transportation department of Santa Clara County, California, announced an opening for a road dispatcher, a position that entailed sending out equipment and crews to maintenance jobs. Among the applicants was a longtime roadyard clerk named Diane Joyce. The department, adhering to its own affirmative-action policies, gave her the job even though several men scored higher on a qualifying examination. One of them, Paul Johnson, claimed discrimination in U.S. District Court, and prevailed.

The clerks of the 9th Circuit expected the court to dispense with the appeal quickly, says Melvin Urofsky, a law professor at Virginia Commonwealth University who wrote a book about the case. “Clearly [Johnson] had been denied the promotion because he was a man,” Urofsky says.

But the 9th Circuit spent hours questioning the parties’ attorneys, and ended up giving greater weight to the department’s history of discrimination against women. “Affirmative action is necessary and lawful…to remedy long-standing imbalances in the workforce,” Fletcher wrote in her 1984 ruling, pointing out that not one of the department’s “skilled craft” workers, including dispatchers and construction inspectors, was a woman.

Until then, in cases such as Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, the nation’s important court rulings on affirmative action had focused on racial preferences in hiring, promotions, and school admissions. They had generally found affirmative action to be constitutional (provided, a la Bakke, that quotas not be used), but Fletcher’s ruling was the first to find that the same standards applied to affirmative action for women. The Supreme Court affirmed Fletcher’s ruling in 1987.

The judge recalls a symposium on the case held at Cornell University not long after. A questioner, referring to the then-novel fact of her being a female judge, asked her: “Don’t you think you should have disqualified yourself?”

“I said, ‘Did the men have to disqualify themselves?'”

The Johnson case far from settled the matter of affirmative action, of course. As cases challenging the practice continue to be litigated, the Supreme Court has largely withdrawn its support. In June, for instance, the court reversed an opinion by Sotomayor, who had upheld affirmative-action practices at a fire department in Connecticut.

“The mantra of the Roberts court is we’re completely color-blind,” Fletcher says. “We don’t need to look at the past.” But Fletcher, who cites the Johnson decision as one of her most notable, holds firm to her belief in the continued importance of affirmative action. “Take all the CEOs in America: What percentage do you think are women?” she asks.

It’s clear that she also disagrees with the prevailing legal view on the death penalty. “We all know what the law is,” she says, referring to cases that have determined that the death penalty is constitutional. “That doesn’t mean it’s morally right.”

In fact, a decade ago, she authored an opinion that overrode a verdict by her fellow 9th Circuit judges and called off an execution two days before it was scheduled. The case involved what she and others considered prosecutorial misconduct. Even so, the Supreme Court slapped down her opinion on procedural grounds, fueling a still-raging argument about whether legal technicalities should trump claims of innocence.

The case stemmed from the 1983 conviction of Thomas Thompson, a California man with no prior arrest record, for the rape and murder of Ginger Fleischli. Prosecutors initially held that Thompson was but an accomplice of another man, Fleischli’s onetime lover David Leitch, who wanted her out of the way so that he could reconcile with his former wife. Leitch was “the only person…who has a motive,” a prosecutor claimed at a pretrial hearing. In support of this theory, the state presented four jailhouse snitches who claimed Thompson had told them how Leitch had recruited him to help with the murder after a night in which they had all gone out drinking.

Yet when the co-defendants had their cases separated, and Thompson was chosen to be tried first, the state changed its story, according to the legal record. The prosecutor contended that Thompson killed Fleischli alone because he had raped her and wanted to cover it up. To support this theory, the prosecutor produced two new and notoriously unreliable jailhouse informants, keeping the others with contradictory stories away from the courthouse. When he secured that conviction and went on to try Leitch, the prosecutor changed his story again. He went back to his old theory, refrained from calling the two snitches he had used to convict Thompson, and instead called defense witnesses from Thompson’s trial whose credibility he had previously tried to impugn.

“Here, little about the trials remained consistent other than the prosecutor’s desire to win at any costs,” Fletcher wrote in her opinion, which determined that Thompson’s right to due process had been violated.

Adding to the controversy was that, by the rules of the court, Fletcher’s opinion had actually been issued late. She and other judges had made their ruling after an “en banc” review—a procedure in which a larger panel of judges rehears a case initially decided by just three. Due to “procedural misunderstandings,” Fletcher explained in her opinion, concerned judges had missed the deadline to call for this review of Thompson’s case. The court went ahead regardless because, Fletcher wrote, “the consequence of our failure to act would be the execution of a person as to whom a grave question exists whether he is innocent.”

The Supreme Court called the procedural unorthodoxy “a grave abuse of discretion.” By interfering with a planned execution after all appeals had been exhausted, the court said, the 9th Circuit was defying almost 13 years of court review and “the entire legal and moral authority” of the state of California. A short time later, Thompson was executed.

Fletcher’s unwavering liberal voice is no longer just part of the chorus on the 9th Circuit. After Carter, Ronald Reagan appointed two prominent conservatives, Kozinski and Diarmuid O’Scannlain. Subsequent presidents, including Clinton, added to the ideological mix by largely appointing either moderates or conservatives. Fletcher’s son, by all accounts, stands to the left in this group, slightly to the right of his mother.

“The 9th Circuit is now evenly balanced, with the vast majority floating in the middle,” says Rosen. “Moving forward, it will be interesting to see which direction Obama takes it in his appointments.” He’s got one vacancy already to fill.

In the meantime, Fletcher holds down the fort on the far left with two other Carter holdouts, Reinhardt and Harry Pregerson.

Among the pressing cases before the court are a number related to George W. Bush’s war on terror, including consolidated claims stemming from warrantless wiretapping. “These cases all present a critical test of the Bush—and now Obama—administration’s sweeping claims of executive authority,” says Ben Wizner, an attorney with the American Civil Liberties Union’s National Security Project. As Wizner notes, Obama’s administration has picked up right where his predecessor left off in these cases, arguing, for instance, that some should be dismissed out of hand in order to avoid airing state secrets.

There’s no telling whether Fletcher herself will be in a position to rule on these cases. The court announces which judges will hear a case only a week before oral arguments; assignments are random. But at the interview in her office, she offers some insight into the scrutiny she might give such claims should she sit on a case. “The question is, who examines that it is in fact a state secret?” She says the courts should do so, through private “in camera” proceedings, rather than trust the government’s assurances.

She’s frank in her suspicion that some of the Bush administration’s activities were illegal, hedging her remarks only slightly. “It’s apparent, or probably apparent, that laws involving search and listening in on people’s private conversation…have been violated,” she says.

Just as with NEPA, Fletcher seems prepared to hold the White House accountable. “The law must be followed,” she says.